Fictivity: The Role of Archetypes

- Mar 31, 2019

- 4 min read

Let’s assume that the idea of Four Basic Life Positions is a basically acceptable one.

That’s the notion that, as we grow up, we adopt a particular narrative as a result of our own personalities and what happens to us: ‘I’m happy in a happy world’, ‘I’m happy in a neutral world’, ’I’m sad in a neutral world’ or

‘I’m sad in a sad world’. These can change of course — indeed, most of our lives are formed by their shifting patterns. We experience overwhelming sadness early in our childhoods, for example, and assume the ‘I’m sad in a sad world’ position, but perhaps equally overwhelming positive experiences later challenge that predisposition and force us to switch our viewpoint; or, alternatively, early happiness is thwarted by later tragedy. Generally, though, at any single point in our lives, we perceive things from one of these four positions.

That includes storytelling.

If we are writers who have as a largely unconscious ‘strategy’ towards life assumed the ‘I’m sad in a sad world’ position, the likelihood is that we will drift towards writing darker fiction. We can see the results in the great fiction all around us, once we know enough about the author’s life to make a judgement: thus we can see Hardy writing from such a position, and can also determine the 'life positions' of Lewis, Tolkien, Le Guin, Huxley, Forster, Hemingway, Orwell, Melville -- basically, any author about whom we know a little. Dickens, for example, is most visibly creating from a ‘I’m happy in a happy world’ position, though a book like Great Expectations capitalises on Dickens’ understanding of human nature and tells a tale of sadness in a sad world. True masters like Shakespeare can write works which appear sound from several positions — and he lived long enough ago to limit speculation as to his own views. But a story which begins in darkness and seems to present a ‘sadness in a sad world’ position, for example, can resonate with emotional power when it switches position with its ending. Think of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol as an example — any story involving what Tolkien called a ‘eucatastrophe’, a sudden turning to the ‘Good’, is undergoing such a switch, with often intense and long-lasting results for readers. Likewise, a story may plunge into despair with emotional consequences.

What matters here is not the psycho-analysis of authors, though, whether they have been successful or not. The key point is understanding the principle, so that it can be used to empower our own fiction writing. And there is much more to this than these Four Positions.

It’s probably fairly easy to arrive at an initial judgement regarding our own works. Do we prefer them to end ‘happily’ or not? Is there an observable trend in them towards darkness and misery? Furthermore, do our protagonists lean towards a reunion with society at the end? Or does ‘all Hell break loose’ and the world drown along with them?

The Four Basic Life Positions relate to the Four Basic Genres, as you can see: Epic, Tragedy, Irony and Comedy are all fictive reflections of the narratives people tend to adopt in life. But what if we want to either strengthen or change our genre? What if — more ambitiously — we want to strengthen or change our own life position?

To do either, we had better get a firm grip on what it is that makes these four genres work in the first place.

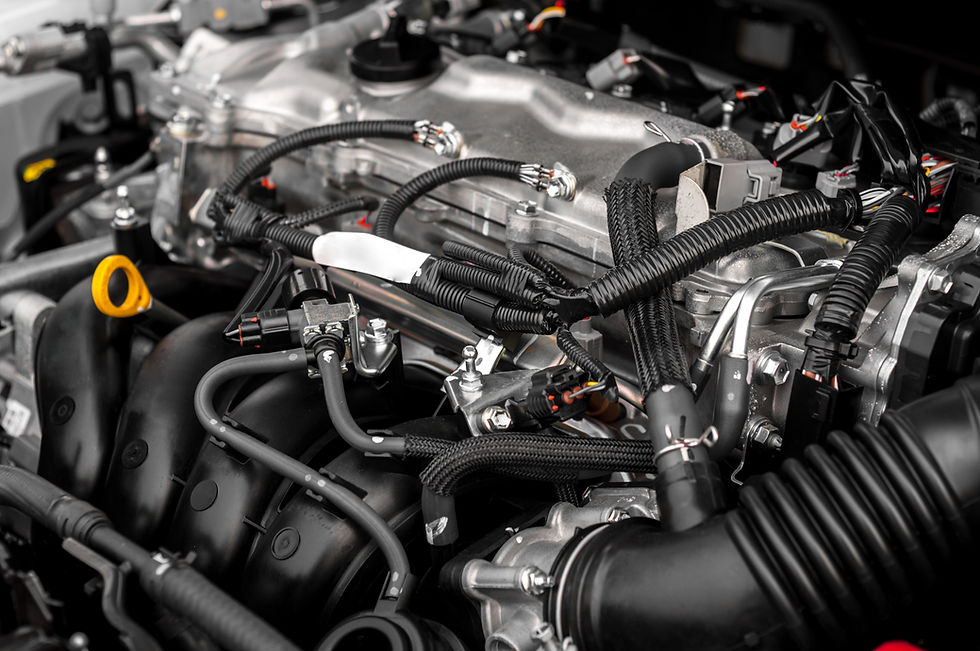

Think of a genre as an engine. Its fuel is reader attention — but its mechanisms consist of working parts which convert that attention into commitment and emotion. You may have read more about this in How Stories Really Work, but let’s take a look at it from a slightly different angle here.

What are these ‘working parts’ which form the inner workings of a genre engine?

Primarily, they are what we call ‘characters’. But by that term, I don’t mean the vague identities which writers conjure up at random in the process of telling a tale, which would be the usual definition — I mean a very precise structure of functioning archetypes, each of which has a particular task to perform in relation to the genre engine of which it is a part.

First among these is the chief ‘attention-attractor’, the protagonist. He or she must contain elements designed to suck in reader attention like a magnet. Readers of How Stories Really Work will recognise these as ‘vacuums’: gaps, holes, missing things, wounds, losses or threats of losses which act powerfully upon readers to draw in attention and ‘trap’ it within the story. The more needy and empty a protagonist is, within the context of a particular tale, the more effective he or she will be in performing her or her function as an archetypal machine part.

This achingly hollow figure is then guided along a channel towards resolution by another archetype: the wise old figure. In Epics, these are clearly visible; in Comedies, less so. In Tragedies, such figures are twisted and dark (think of Macbeth’s witches), while in Ironies they become pathetic and doomed creatures (as does everyone in an Irony). But they serve in each case to impel the protagonist forward.

Other parts of the genre machine include the Emerging Warrior, the Submerged Companion, the Shadow Protagonist and of course the Antagonist, each performing particular functions in relation to the whole so that the overall result of each genre is produced: in Ironies, nightmare; in Tragedies, sorrow; in Comedies laughter and reunion; in Epics, victory. All of this and more is covered elsewhere.

What is fascinating is the possible correlation between these functions and their archetypes in fiction and the underlying Four Basic Positions of Life itself. In other words, we have seen how character archetypes play out their roles in stories, something which can be demonstrated time and time again throughout the worlds of fiction for as long as human beings have written anything — but what is less demonstrable, at least so far, is the role played by such figures in the foundational narratives which mould writers’ own worlds.

More to follow.

Comments