The 'Marvel Method'

- Dec 11, 2022

- 3 min read

There may be things we can learn from the wonderful world of comics when it comes to putting a story together. Comics obviously use both a plotter and an artist - though sometimes these are the same person - but the way that these two aspects of a story can work together can serve to illustrate certain things about a piece of fiction which we might not be able to grasp in any other way.

The classic method of producing a comic book story, as used by DC Comics for decades, started with the plotter or writer. He (or much more rarely, she) would break the story down in sequence, page-by-page, panel-by-panel, describing the action, characters, and even sometimes what should lie in the background of each panel and from which point of view it should all be seen. In addition, all captions and dialogue balloons would be specified. This led to a neat but rather ‘fixed’ and formal look for the resulting comic. This is much more like the traditional way of writing a novel, with the visual part of the story being no more than an illustration of what the words were saying.

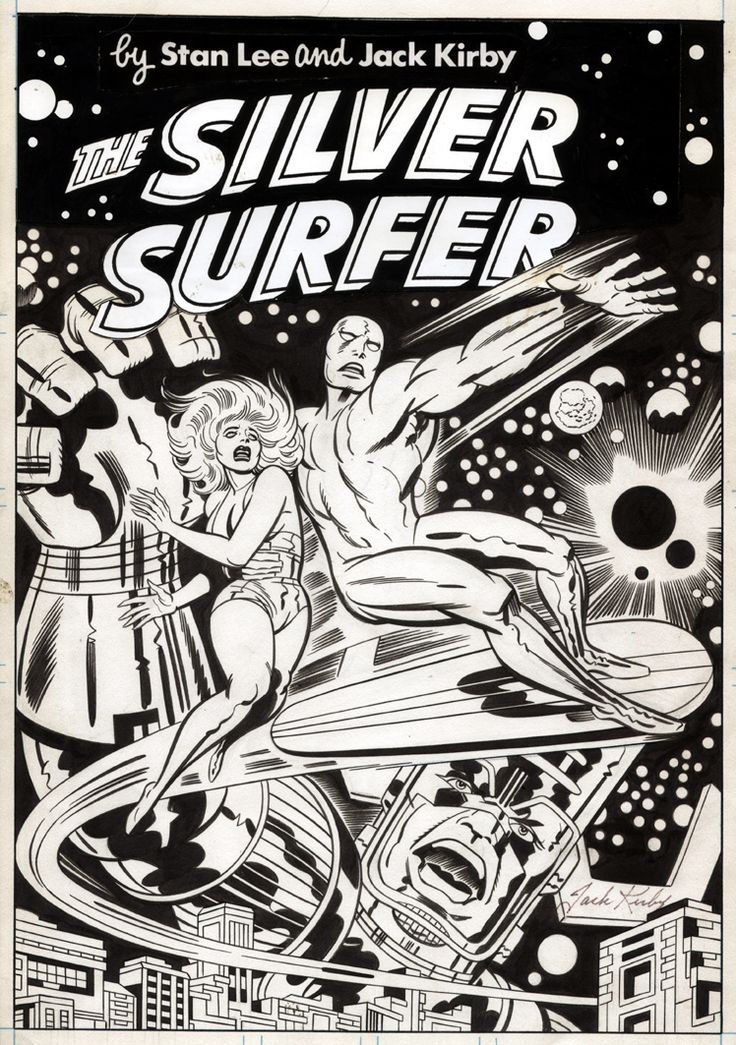

Stan Lee, creator and co-creator of some of the most popular comic book characters and stories of all time, is credited with also having introduced the ‘plot script’ method which became known as the ‘Marvel Method’ or ‘Marvel House Style’. In a plot script the artist works from a story synopsis from the writer or plotter. Using only this rough outline of a story, the artist then creates page-by-page panels through which the plot develops, after which the work is returned to the writer for the insertion of dialogue. It’s a kind of ‘ghost writing’ in a new form: the writer generates the basic plot but the details are completely created by another person.

This method supposedly arose because Lee was overloaded with work. Rather than have time to develop full scripts, he started handing over outlines to artists like Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko, relying on their story-telling abilities to bring the thing to life. The result was a more flowing, cinematic style: instead of panels being carefully composed by a writer, the artist was freer to explore scenes from unusual angles and to create variations in the sequence of a tale.

The whole method was very flexible, depending on how much detail the writer wanted to put into the synopsis: these varied from one page in length to twenty-two, apparently. For example, when working with Ditko on Amazing Fantasy and other pre-superhero Marvel science-fiction/fantasy anthology titles, Lee later said, ‘I'd dream up odd fantasy tales with an O. Henry type twist ending. All I had to do was give Steve a one-line description of the plot and he'd be off and running. He'd take those skeleton outlines I had given him and turn them into classic little works of art that ended up being far cooler than I had any right to expect.’

Apart from giving the writer more time and the artist more freedom, the ‘look’ of comics was changed by this approach, with stories leaning towards more visual interpretations.

As writers, I wonder if it would be possible to learn from this and to split ourselves into two halves - one acting as an ‘outliner’, giving only the loose framework in which a story is to take place, while the other concentrates on the visual elements of a story: from what viewpoint could a scene be viewed? How could the story unfold as to be more visually exciting? How far could the rough outline be stretched in new, unexpected directions? Then, having achieved a more detailed version of the story, we could hand the whole thing back to the ‘writer’ part of ourselves for the addition of dialogue and other details.

It would be an interesting experiment, and is probably how screenwriters think when putting a tale together.

Games like Doors or Piggy rely on environment, pacing, and visual cues to tell the story first, similar to the Marvel Method, where structure comes from visuals and the narrative details are added later.

This approach is easy to recognize in Roblox APK game design. Many developers start with a simple outline of the game idea, then build the experience visually through level design, camera angles, and player movement before adding dialogue or story text.

geometry dash lite is a rhythm platform game where players tap to jump, dodge spikes, follow music beats, complete levels, earn stars, and test fast reactions.